From time to time, we hear individuals, including ourselves, express the feeling of their brains being overwhelmed. This sensation isn’t surprising considering the myriad intricate tasks our brains handle. These tasks encompass learning, planning, memory retention, communication, sight, hearing, and even olfaction.

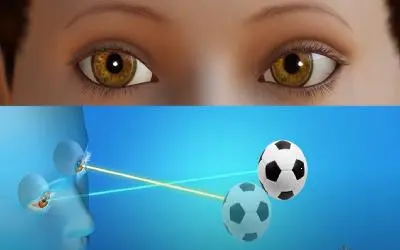

It’s no shocker that an increasing number of studies establish a correlation between compromised sensory functions, such as poor vision and hearing, and a decline in cognitive abilities. The brain seems to have limits, and when it struggles to interpret the world—from deciphering written words to comprehending speech—it may compromise other vital functions.

Though a definitive cause-and-effect relationship is yet to be established, mounting evidence suggests that uncorrected deficiencies in vision and hearing may hasten cognitive decline.

National data underscores the significance of this connection. Projections indicate a doubling in the number of Americans with poor vision, often undiagnosed in older adults, by 2050. Hearing loss, largely untreated or undertreated, affects nearly two-thirds of adults over 70. Moreover, one in nine individuals aged 80 and above experiences both vision and hearing impairment, while less than one in five have neither. Alarmingly, dementia prevalence is doubling every two decades.

A recent study published in JAMA Ophthalmology involved a representative sample of nearly 3,000 older Americans and another sample of 30,000 Medicare beneficiaries. The findings from different measurements of cognitive abilities like memory, orientation, and planning suggested a real association between vision impairment and compromised brain function.

Dr. Suzann Pershing, the lead author and an ophthalmologist at Stanford University School of Medicine, noted that while this association doesn’t conclusively prove that vision loss causes cognitive decline, intuitively, less engagement with the world might lead to reduced cognitive stimulation and subsequent decline in cognitive function.

A prior University of Michigan study by Dr. Mary A.M. Rogers and Kenneth M. Langa involving 625 elderly people found that those with poor vision faced a 63 percent higher risk of developing dementia over eight and a half years. Additionally, those with poor vision who didn’t consult an ophthalmologist were five times more likely to experience cognitive decline and nearly ten times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Dr. Pershing highlighted that improving the vision of individuals with cognitive impairment could enhance their functionality.

Similarly, evidence suggests a strong link between hearing loss and accelerated cognitive decline. Yet, it remains uncertain whether properly adjusted hearing aids can lower dementia risk or delay its onset. A study sponsored by the National Institute on Aging aims to determine in five years whether using hearing aids can preserve brain function in aging individuals with hearing loss.

Dr. Frank R. Lin, an otolaryngologist at the Johns Hopkins Center on Aging and Health, emphasized the potential impact, particularly in the current landscape. Tech companies like Apple and Samsung are anticipated to introduce affordable hearing aids, significantly reducing costs from $5,000 to possibly $50–$300 per pair. Additionally, Dr. Lin highlighted Costco’s efforts in affordability by lowering the cost of hearing aids fitted and serviced by skilled audiologists.

Meanwhile, existing knowledge suggests that older adults experiencing hearing loss face a 24 percent higher likelihood of cognitive decline within six years compared to those with normal hearing. Their cognitive abilities decline up to 40 percent faster than counterparts with normal hearing. Furthermore, they encounter issues with thinking and memory functions, developing them nearly three years earlier than those with normal hearing. The severity of their hearing loss correlates with greater cognitive decline over time.

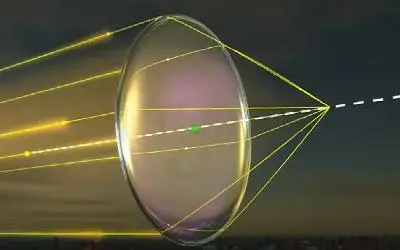

Dr. Lin delineated three potential explanations for the link between poor hearing and dementia. Firstly, “cognitive load” occurs when unclear signals reach the brain, compelling it to work harder to decipher messages. Secondly, individuals with hearing difficulties tend to isolate themselves socially, reducing cognitive stimulation. Thirdly, brain structure alterations, especially over the hearing portion of the brain involved in memory and learning, may lead to faster brain atrophy.

Functional MRI studies at Washington University in St. Louis, conducted by Jonathan Peelle and colleagues, revealed that even mild hearing loss prompts increased activity in the frontal cortex—an area associated with thinking and decision-making. Advanced hearing loss, on the other hand, leads to shrinking of the auditory cortex, potentially impeding tasks beyond hearing.

While the cost-effectiveness of routine vision and hearing screenings for older adults remains unproven, experts advocate for periodic exams to detect correctable issues that could reduce dementia risk and enhance overall quality of life.

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends comprehensive eye exams every two to four years for individuals aged 40–54 without symptoms or risk factors for vision loss, increasing the frequency to every one to three years for those aged 55–64, and annually or biennially thereafter. These exams aid in preserving vision by identifying treatable conditions like glaucoma, cataracts, and age-related macular degeneration.

Likewise, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association advises a hearing test at least every decade through age 50 and every three years thereafter. As Dr. Lin highlighted, hearing loss can progress gradually, often unrecognized until it’s considerably advanced. Therefore, undergoing tests presents no harm and may detect issues early.

Consider scheduling an appointment with our vision specialist to explore the connection between your vision and auditory input.