Services

VISUAL SPATIAL ORIENTATION SKILLS

Visual spatial orientation, a fundamental aspect of perceptual-motor development, encompasses the profound awareness of one’s position within the spatial context of surrounding objects, as well as the relative locations of these objects in relation to one another. This multifaceted skill set extends beyond mere spatial perception to include body awareness, control, and bimanual integration.

At its core, visual spatial orientation entails the capacity to comprehend directional concepts, both within one’s internal perception and when projected into the external visual space. It’s a fundamental skill that plays a pivotal role in various aspects of daily life. For instance, it underpins our ability to maintain balance, execute coordinated body movements, and navigate effectively in our environment.

Moreover, visual spatial orientation skills are instrumental in following spatial directions, such as interpreting maps or instructions, and understanding the orientation of alphanumeric symbols, which are vital in tasks ranging from reading and writing to interpreting complex graphical information.

In essence, this intricate cognitive skill facilitates our interaction with the world, helping us make sense of our surroundings and allowing for coordinated, purposeful actions.

VISUAL ANALYSIS DYSFUNCTION

Efficiently analyzing and interpreting visual information is a crucial cognitive ability often termed ‘visual perception.’ Non-motor visual analysis skills encompass a set of dynamic processes that involve locating, selecting, extracting, analyzing, recalling, and manipulating pertinent information within the visual environment. These processes serve as foundational skills for tasks such as recognizing letters and numbers, building sight word vocabulary, and grasping mathematical concepts. Traditionally, non-motor visual analysis skills have been categorized into distinct theoretical constructs, including visual discrimination, visual figure-ground discrimination, visual closure, visual memory, and visualization.

VISUAL-MOTOR INTEGRATION

Visual-motor integration, also known as visually guided motor response, encompasses the capacity to harmonize the processing of visual information with precise fine motor actions. It involves the translation of abstract visual data into corresponding fine motor activities, typically related to hand movements like copying and writing. Visual-motor integration comprises three distinct processes: the analysis of visual stimuli, fine motor control (involving eye-hand coordination), and visual conceptualization, which encompasses the integration process itself. Any deficits within these processes can impact the overall outcome. Consequently, assessing fine motor coordination is essential for an accurate diagnosis. For instance, if visual analysis and fine motor coordination skills fall within the normal range but there are issues with visual-motor integration, the challenges are primarily linked to the integration-processing phase.

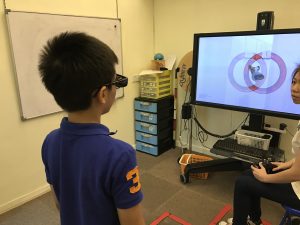

How are Visual Information Processing deficits treated?

Scientific research has established the effectiveness of vision therapy in addressing visual processing deficits, even in cases where patients have suffered brain injuries. Individuals with a history of brain injury or organic conditions may exhibit deficiencies in various aspects of visual information processing. While therapy can pose greater challenges for patients with brain injuries, it serves as a compelling testament to the efficacy of vision therapy in addressing visual processing disorders. Numerous studies drawn from neurological, optometric, and occupational therapy sources further underscore the positive impact of visual processing therapy and training on addressing these deficits.

Who is qualified to assess Visual Information Processing Disorders?

Raymond et al. recommend that the assessment of visual processing should be done by Board Certified Neuro-Developmental & Behavioral Optometrist – not an ophthalmologist. The ophthalmologist, according to the authors, does not have the expertise to make the assessment. The study authors note that patients:

“should be referred to a Board Certified Behavioral & Neuro-Developmental Optometrist. It was also noted that referrals made to an ophthalmologist may be insufficient, as they are primarily concerned with the health of the eye only, and ophthalmologists are mostly experienced with acute medical problems rather than rehabilitation issues. This assertion is supported by considering the typical components of an ophthalmologic exam, which may yield a lack of specificity, and/or provide information which is inadequately defined in terms of rehabilitation consequence. Trobe, Acosta, Kirscher and Trick identify a lack of measurement in areas of distance and near acuities, contrast sensitivity and confrontation, while Gianutsos and Matheson describe a need for greater quantification in terms of field gradations and boundaries, and binocularity conditions. A more thorough investigation is important for the rehabilitative efforts of all patients who demonstrate visual processing deficits.”

The study’s authors go on to note that “[o]phthalmologists are excellent surgeons and expert at treating acute disease but their expertise does not to extend to the diagnosis or treatment of visual processing deficits.“

Do Visual Information Processing Deficits impacts academic performance?

Numerous studies affirm the affirmative stance.

For instance, a 2005 study by Goldstand et al. titled “Vision, Visual Information Processing, and Academic Performance Among Seventh-Grade Schoolchildren: A More Significant Relationship Than We Thought?” and published in The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, offers a compelling example. This research, conducted by experts in behavioral optometry and occupational therapy, aimed to compare visual and visual information processing abilities among seventh-grade students with and without mild reading and academic difficulties. The study revealed that visual function plays a significant role in distinguishing children with mild academic challenges from those without, particularly in terms of visual-perception scores.

Another study conducted by Kulup et al. in 2002, published in Optometry and Vision Science, delved into the relationship between poor visual memory (a component of visual information processing) and subpar performance in reading decoding, mathematics, and overall academic achievement, as assessed by the Stanford Achievement Test. This relationship held true for second- through fourth-grade children, even after accounting for age and verbal ability.

Download below pdf for more information.