Difficulties with reading and attention often become more noticeable after the third grade, particularly as students increasingly rely on written materials to aid their learning. Progressing into middle and high school, these challenges may transform an enthusiastic reader into someone who avoids reading altogether. Educational teams might question why a capable student is not making expected reading progress despite intervention efforts. While various factors could hinder a student’s progress, such as using inappropriate interventions, incorrectly implementing interventions, or attention/processing/cognitive deficits, sometimes the difficulties may be linked to vision deficits.

As students advance through the K-12 system, the materials they encounter typically transition from “sans serif” fonts (like Arial or Comic Sans) to smaller-sized or “serif” fonts (e.g., Times Roman). Alongside font changes, the spacing between lines often decreases (e.g., from single line to 1.5 lines). While most students adjust well to these presentation changes, some find them challenging, making reading more difficult and sometimes impeding or stopping reading progress. When persistent or emerging reading issues arise, schools and parents often investigate whether vision deficits could be contributing factors.

A vision deficit might be present even if a student has 20/20 eyesight. Common eye exams in schools or pediatrician offices use versions of the “Snellen eye chart” (from the 1800s) or the LogMAR chart (from 1976) to assess a student’s near and far vision. However, these traditional exams primarily measure visual acuity and typically do not assess how long a student’s eyes can focus on text without fatigue, their ability to focus quickly to read, or difficulties reading or tracking multiple lines on a page. Students with vision issues might have 20/20 vision in a controlled testing environment, but in the classroom or at home, they may:

- blink or rub their eyes frequently,

- complain they are tired or have a headache,

- have burning, teary or itchy eyes,

- feel nauseous when reading,

- not pay attention,

- experience a “clicking” movement when their eyes move back and forth,

- visually jump around on a page or skips lines when they try to read,

- lose their place when reading,

- need to use a finger to help them track when reading,

- have poor handwriting and letter placement on lined paper,

- tilt their head when reading,

- complain that the words jump around, fade in or out, or are blurred,

- omit or misread words, or

- have troubles copying images.

The COVD-QOL checklist (College of Optometry Vision Development – “Quality of Life” Checklist) is a widely used tool for assessing non-acuity vision development issues. San Diego Unified utilizes its Checklist of Visual Behavior, which encompasses much of the COVD checklist. If a student demonstrates any of the previously mentioned indicators, they might be mistakenly seen as having ADHD or another learning disability when, in reality, they may have a vision deficit in one or more of the following areas:

Fixation: The ability to quickly focus on an object and shift attention to another.

Convergence: The capacity to turn the eyes inward for reading and maintain eye alignment during extended reading periods.

Tracking: The skill to follow objects visually, especially during reading or sports activities.

Binocular vision: Proper utilization of both eyes to process information.

Stereopsis: The ability to determine distances between objects.

Form perception: The capability to recognize differences between objects for mental organization.

Field of Vision: The eye’s ability to gather information from an appropriate visual field.

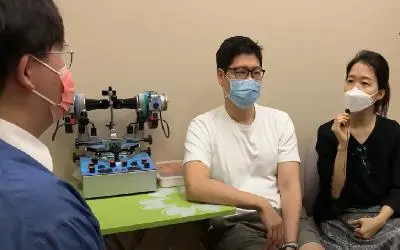

If a student experiences some of the aforementioned physical symptoms and struggles with focusing and reading, the educational team should consider discussing whether a “developmental vision assessment” is necessary. Should an assessment reveal difficulties in eye movement control, eye alignment, eye teaming, or refraction, the student’s IEP team should consider vision therapy.

In California, “vision services” are part of special education services if the student has an IEP, and the team believes the student’s vision impacts their educational performance (Ca. Ed. Code § 56363(b)(7)). Vision therapy in California may involve remedial or developmental instruction provided by or in consultation with qualified medical professionals, including optometrists, ophthalmologists, or licensed physicians and surgeons. School personnel may also offer such therapy as directed by a qualified medical professional (5 CCR § 3051.75).

School districts are responsible for assessing students suspected of disabilities when their performance falls below their potential. If there are concerns about a child or student experiencing learning difficulties, requesting a developmental vision exam could help explore potential vision deficits. Parents should formally request an assessment, providing reasons, and submit it to the child’s teacher or case manager. Districts like San Diego Unified School District have specific procedures detailing the responsibilities of the case manager and IEP team, which parents should familiarize themselves with before making a request.

Sample Resources:

College of Optometrists in Vision Development

Study on the use of COVD-QOL for screening

Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments for Convergence Insufficiency in Children (2005)

Vision therapy in adults with convergence insufficiency (Optometry Vision Science, 12/10, abstract posted by National Institute of Health)

Efficacy of vision therapy for convergence insufficiency in the adult male population, Journal of American Optometry Association, April 1999 (Conclusion: Vision therapy is effective in eliminating asthenopia and improving convergence function in adult patients. In-office therapy combined with home therapy tends to produce better results than does home therapy alone).

American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus

Vision Therapy FAQs (Optometrists Network)

Videos showing vision therapy (WebMD)

Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD, ADHD) and Vision

CNN Report: “Seeing Straight” (12/22/09)

Vision therapy ideas on pin interest

Vision Therapy Blog

Presentation on how to use apps in vision therapy

Sample Vision Therapy Games

Sample vision apps

All About Vision

A patient’s guide to insurance coverage for vision therapy