Services

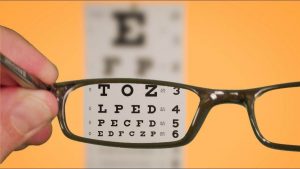

Eyesight is the capacity to perceive objects with clarity, often quantified as 20/20 eyesight in a standard eye examination using a Snellen chart. Vision, on the other hand, transcends mere eyesight and can be defined as the comprehension of what is perceived. Vision encompasses the ability to receive visual input, process that information, and derive meaning from it.

Two fundamental observations can be made about vision. Firstly, vision is acquired through learning. Much like a child learns to walk and talk, they also learn to see. In the process of acquiring these skills, children have the advantage of emulating their parents and siblings. Furthermore, parents can monitor their children’s progress in walking and talking. In contrast, the development of vision generally occurs with less overt parental involvement or awareness. These disparities in developmental processes result in each individual having a unique way of perceiving the world.

VISION EYESIGHT IS LEARNED

Visual perception is a learned skill, which means it can be developed and improved through training. If a child lacks essential visual abilities, they can acquire them through guided Vision Therapy activities and exercises, overseen by Vision therapists and supervised by Behavioral and Developmental Optometrists.

HAVING SUFFICIENT VISION IS ESSENTIAL FOR LEARNING PROCESS

As approximately 75% to 90% of a child’s learning is mediated through their visual system, it becomes evident that any disruptions in these pathways could lead to learning-related vision challenges. Consequently, these challenges may hinder a child’s ability to reach their full developmental potential.

VISION

Visual Acuity

Numerous visual skills play a vital role in achieving academic success, with visual acuity (clarity and sharpness) often considered one of the less critical factors. Visual acuity is commonly represented as 20/20, 20/400, and the like, indicating an individual’s ability to see clearly at a distance of twenty feet. However, it’s important to recognize that a child’s visual acuity at a distance of twenty feet may not accurately reflect the functionality of their vision at the reading and learning distance, typically ranging from eleven to sixteen inches from their face. In my view, the use of the Snellen eye chart test, which primarily assesses visual acuity at a distance, can be counterproductive. It can create a false sense of reassurance for both parents and teachers regarding the normalcy of a child’s vision. It’s crucial to acknowledge that there are numerous other critical visual skills that may remain underdeveloped, even when distance visual acuity appears to be within the normal range.

Binocular Coordination

An essential visual skill is the capacity to effectively coordinate both eyes. While a child is born with two eyes, they must acquire the ability to harmonize their eye movements. Not all children achieve this coordination equally well. For instance, some children may encounter a condition called exophoria, characterized by a tendency for the eyes to diverge outward. It’s important to note that this differs from exotropia, where one eye is visibly misaligned outward.Adequate Convergence

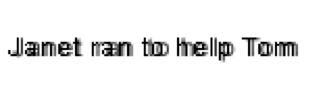

During the act of reading, the demand placed on the eyes is to converge or turn inward, aligning them to focus on the text. When there’s a tendency for the eyes to deviate outward, a child must exert additional effort and energy to maintain their focus on the reading material. Numerous studies have demonstrated that increased effort in reading is associated with reduced comprehension and overall performance. In the process of reading, the eyes don’t move smoothly across the text; instead, they make a series of fixations, shifting from one word to the next. In the presence of exophoria, each time fixation is disrupted and the eyes move to the next word, they tend to diverge outward and need to be realigned to regain focus. Typically, children naturally develop an aversion to reading under these conditions. This aversion is compounded by the fact that children often prefer to avoid tasks they find challenging. Consequently, these children might gaze out the window instead of maintaining visual attention. They are often unfairly labeled with terms like having a short attention span, lack of effort, dyslexia, minimal brain dysfunction, or learning disabilities. Frequently, they lose their place while reading and may resort to using their finger or a marker to help maintain their position. During the eye movements required for reading, they might not land precisely on the next word, leading to omissions or confusion of small words. Sometimes, they may even insert additional words to make sentences coherent. When both eyes are correctly aligned and focused on the same point in space, an individual perceives the fixated object as single. However, if the eyes do not precisely converge on the same point, double vision or overlapping vision (as shown in Figure #3) can occur. It’s important to note that children with these vision challenges may not be able to articulate that their vision is unclear because they lack a reference point to compare their vision with that of others.

Astigmatism,Eye-Hand Coordination, Visual-Motor Problems and more

For many years, I have asserted my ability to enter a classroom and identify children experiencing visual coordination difficulties. These children tend to adopt contorted postures in an effort to alleviate the strain on one of their eyes. They may be seen resting their head on their arm, covering one eye with their palm, or tilting their head in a way that obstructs the vision from one of their eyes.Esophoria

Another eye coordination issue is referred to as esophoria, characterized by an inward turning of the eyes. The educational consequence of this condition is that a child with esophoria perceives objects as smaller than their actual size. To view an object accurately, it becomes necessary to enlarge it, and the only method available to the child for achieving this is to bring the object closer. Consequently, one might observe the child with their head buried in a book, yet still struggling to attain a clear view. Reading Skills and Binocular Visual Skills One of the assessments conducted in optometric offices involves having the child read words while using a device known as a Telebinocular. During this test, the child’s reading performance is compared when using each eye separately and when using both eyes together. A significant disparity in performance often emerges when there is an issue with eye coordination. While one eye may perform adequately on its own, reading with both eyes together can result in slower reading speed and a higher number of errors. Other Visual SkillsDirectionality

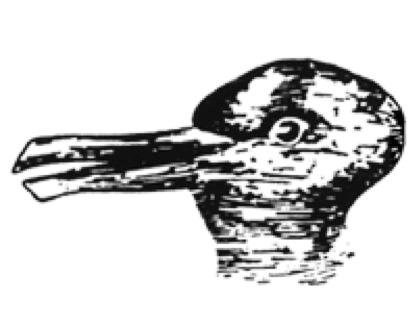

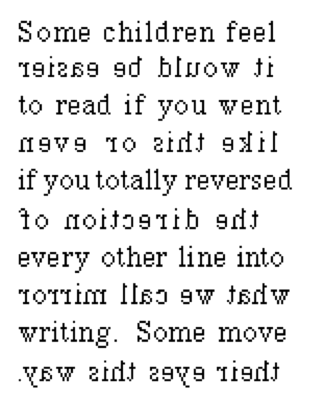

Directionality is another critical visual skill essential for academic success. An example of a test to assess this skill is depicted in Figure #5. Please examine Figure #5 and discern what you perceive. If your visual perception goes from left to right, you will see a duck. Conversely, if your visual perception goes from right to left, you will see a rabbit. This is just one of several tests used to evaluate the directionality of the visual reflex. Our culture has established a convention where the English language is read from left to right. However, it’s important to acknowledge that other languages follow different reading directions, with some proceeding from right to left, and others adopting a vertical orientation. Many individuals believe that an alternative arrangement, as depicted in Figure #6, would make more logical sense.

If a child does not naturally progress in a left-to-right reading direction, Vision Therapy, overseen by Vision therapists and Behavioral & Developmental Optometrists, can help them acquire this skill. Similar to how a child can learn to coordinate their eyes through therapy, they can also learn to align their reading direction to match cultural norms.

Our culture has established a convention where the English language is read from left to right. However, it’s important to acknowledge that other languages follow different reading directions, with some proceeding from right to left, and others adopting a vertical orientation. Many individuals believe that an alternative arrangement, as depicted in Figure #6, would make more logical sense.

If a child does not naturally progress in a left-to-right reading direction, Vision Therapy, overseen by Vision therapists and Behavioral & Developmental Optometrists, can help them acquire this skill. Similar to how a child can learn to coordinate their eyes through therapy, they can also learn to align their reading direction to match cultural norms.

Form Perception

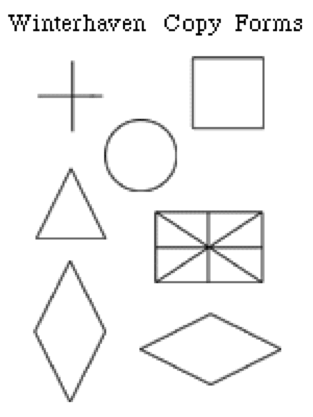

Form perception is another crucial visual skill essential for academic success. An effective way to illustrate this is by referring to Figure #7. In this exercise, the child is presented with these forms individually and is tasked with simply replicating them. It’s astonishing to observe the distortions that may arise as the child attempts to reproduce these forms. When a child struggles to perceive and replicate these basic geometric shapes, it becomes unreasonable to assume that they will effortlessly discern the intricate, curving lines that constitute letters, which then form words, sentences, and abstract ideas. It is not uncommon to encounter children who find it challenging to differentiate between a square and a rectangle, or a circle and an oval. Fortunately, this skill can also be enhanced through Vision Therapy.

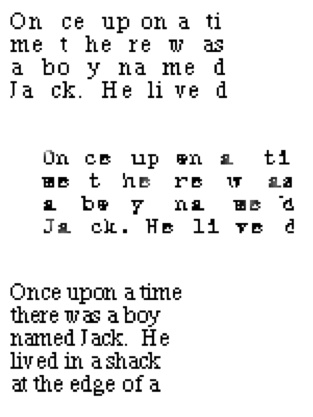

Attention Span/ Span of Perception

The Span of Perception is another factor linked to academic achievement. Some children have the tendency to focus on just one word at a time during each eye fixation. Enhancing reading speed involves acquiring the ability to perceive and process two, three, or even more words with each eye fixation, akin to reading through a wider lens. This concept is visually demonstrated in Figure #8. It’s evident how a broader span of perception can significantly impact one’s ability to comprehend and derive meaning from their reading.